U.S. hospitals, public health authorities, and digital health companies have quickly deployed online symptom checkers to screen patients for signs of Covid-19. The idea is simple: By using a chatbot powered by artificial intelligence, they can keep anxious patients from inundating emergency rooms and deliver sound health advice from afar.

Or at least that was the pitch.

Late last week, a colleague and I drilled more than a half-dozen chatbots on a common set of symptoms — fever, sore throat, runny nose — to assess how they worked and the consistency and clarity of their advice. What I got back was a conflicting, sometimes confusing, patchwork of information about the level of risk posed by these symptoms and what I should do about them.

advertisement

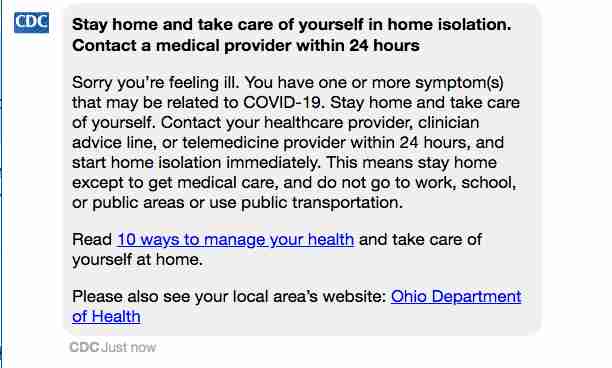

A chatbot posted on the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that I had “one or more symptom(s) that may be related to COVID-19” and advised me to contact a health care provider within 24 hours “and start home isolation immediately.”

But a symptom checker from Buoy Health, which says it is based on current CDC guidelines, found that my “risk of a serious Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection is low right now” and told me to keep monitoring my symptoms and check back if anything changes. Others concluded I was at “medium risk” or “might have the infection.”

advertisement

Most people will probably consult just one of these bots, not eight different versions as I did. But experts on epidemiology and the use of artificial intelligence in medicine said the wide variability in their responses undermines the value of automated symptom checkers to advise people at a time when — above all else — they are looking for reliable information and clear guidance.

“These tools generally make me sort of nervous because it’s very hard to validate how accurate they are,” said Andrew Beam, an artificial intelligence researcher in the department of epidemiology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. “If you don’t really know how good the tool is, it’s hard to understand if you’re actually helping or hurting from a public health perspective.”

The rush to deploy these chatbots underscores a broader tension in the coronavirus outbreak between the desire of technology companies and digital health startups to pitch new software solutions in the face of a fast-moving and unprecedented crisis, and the solemn duty of medical professionals to ensure that these interventions truly benefit patients and don’t cause harm or spread misinformation. A 2015 study published by researchers at Harvard and several Boston hospitals found that symptom checkers for a range of conditions often reach errant conclusions when used for triage and diagnosis.

Told of STAT’s findings, Buoy’s chief executive, Andrew Le, said he would synchronize the company’s symptom checker with the CDC’s. “Now that they have a tool, we are going to use it and adopt the same kind of screening protocols that they suggest and put it on ours,” he said. “This is probably just a discrepancy in time, because we’ve been attending all of their calls and trying to stay as close to their guidelines as possible.”

The CDC did not respond to a request for comment.

Before I continue, I should note that neither I nor my colleague is feeling ill. We devised a simple test to assess the chatbots and limited the experiment to the web- and smartphone-based tools themselves so as not to waste the time of front-line clinicians. We chose a set of symptoms that were general enough to be any number of things, from a common cold, to the flu, to yes, coronavirus. The CDC says the early symptoms of Covid-19 are fever, cough, and shortness of breath.

The differences in the advice we received are understandable to an extent, given that these chatbots are designed for slightly different purposes — some are meant to determine the risk of coronavirus infection, and others seek to triage patients or assess whether they should be tested. They also collect and analyze different pieces of information. Buoy’s bot asked me more than 30 questions, while Cleveland Clinic’s — and bots created by several other providers — posed fewer than 10.

But the widely varying recommendations highlighted the difficulty of distinguishing coronavirus from more common illnesses, and delivering consistent advice to patients.

The Cleveland Clinic’s tool determined that I was at “medium risk” and should either take an online questionnaire, set up a virtual visit, or call my primary care physician. Amy Merino, a physician and the clinic’s chief medical information officer, said the tool is designed to package the CDC’s guidelines in an interactive experience. “We do think that as we learn more, we can optimize these tools to enable patients to provide additional personal details to personalize the results,” she said.

Meanwhile, another tool created by Verily, Alphabet’s life sciences arm, to help determine who in certain northern California counties should be tested for Covid-19, concluded that my San Francisco-based colleague, who typed in the same set of symptoms, was not eligible for testing.

But in the next sentence, the chatbot said: “Please note that this is not a recommendation of whether you should be tested.” In other words, a non-recommendation recommendation.

A spokeswoman for Verily wrote in an email that the language the company uses is meant to reinforce that the screening tool is “complementary to testing happening in a clinical care situation.” She wrote that more than 12,000 people have completed the online screening exam, which is based on criteria provided by the California Department of Public Health.

The challenge facing creators of chatbots is magnified when it comes to products that are built on limited data and guidelines that are changing by the minute, including which symptoms characterize infection and how patients should be treated. A non-peer-reviewed study published online Friday by researchers at Stanford University found that using symptoms alone to distinguish between respiratory infections was only marginally effective.

“A week ago, if you had a chatbot that was saying, ‘Here are the current recommendations,’ it would be unrecognizable from where we are today, because things have just moved so rapidly,” said Karandeep Singh, a physician and professor at the University of Michigan who researches artificial intelligence and digital health tools. “Everyone is rethinking things right now and there’s a lot of uncertainty.”

To keep up, chatbot developers will have to constantly update their products, which rely on branching logic or statistical inference to deliver information based on knowledge that is encoded into them. That means keeping up to date on new data that are being published every day on the number of Covid-19 cases in different parts of the world, who should be tested based on available resources, and the severity of illness it is causing in different types of people.

Differences I found in the information being collected by the chatbots seemed to reflect the challenges of keeping current. All asked if I had traveled to China or Iran, but that’s where commonality ended. The Cleveland Clinic asked whether I had visited a single country in Europe — Italy, which has the second most confirmed Covid-19 cases in the world — while Buoy asked whether I had visited any European country. Providence St. Joseph Health, a hospital network based in Washington state, broke out a list of several countries in Europe, including Italy, Spain, France, and Germany.

After STAT inquired about limiting its chatbot’s focus to Italy, Cleveland Clinic updated its tool to include the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the 26 European countries included in the Schengen area.

The differences also included the symptoms they asked about and the granularity of information they were capable of collecting and analyzing. Buoy’s bot, which suggested I had a common cold, was able to collect detailed information, such as specific temperature ranges associated with my fever and whether my sore throat was moderate or severe.

But Providence St. Joseph asked only whether I had experienced any one of several symptoms, including fever, sore throat, runny nose, cough, or body aches. I checked yes to that question, and no to queries about whether I had traveled to an affected country or come in contact with someone with a lab-confirmed case of Covid-19. The bot (built, like the CDC one, with tools from Microsoft) offered the following conclusion: “You might be infected with the coronavirus. Please do one of the following — call your primary care physician to schedule an evaluation” or “call 911 for a life threatening emergency.”

All of the chatbots I consulted included some form of disclaimer urging users to contact their doctors or otherwise consult with medical professionals when making decisions about their care. But the fact that most offered a menu of fairly obvious options about what I should do seemed to undercut the value of the exercise.

Beam, the professor at Harvard, said putting out inaccurate or confusing information in the middle of a public health crisis can result in severe consequences.

“If you’re too sensitive, and you’re sending everyone to the emergency room, you’re going to overwhelm the health system,” he said. “Likewise, if you’re not sensitive enough, you could be telling people who are ill that they don’t need emergency medical care. It’s certainly no replacement for picking up the phone and calling your primary care physician.”

If anyone would be enthusiastic about the possibilities of deploying artificial intelligence in epidemiology, Beam would be the guy. His research is focused on applying AI in ways that help improve the understanding of infectious diseases and the threat they pose. And even though he said the effort to deploy automated screening tools is well intentioned — and that digital health companies can help stretch resources in the face of Covid-19 — he cautioned providers to be careful not to get ahead of the technology’s capabilities.

“My sense is that we should err to the centralized expertise of public health experts instead of giving people 1,000 different messages they don’t know what to do with,” he said. “I want to take this kind of technology and integrate it with traditional epidemiology and public health techniques.”

“In the long run I’m very bullish on these two worlds becoming integrated with one another,” he added. “But we’re not there yet.”

Erin Brodwin contributed reporting.

This is part of a yearlong series of articles exploring the use of artificial intelligence in health care that is partly funded by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund.

The name “chatbot” should be indicative of what to expect. There simply is not sufficient detail on Covid-19 to build an AI model with reliable answers. Substantial clinics and health centres using this technology at this time are essentially not doing a service to the users. It is way too early for this.

Most experiments would have a control group !! While I’m no fan of chatbots, did you call 8 local doctor’s offices or state DoH hotline and compare their recommendations with those of the bots ?