A common complaint propagated by anti-GMO activists is that Bayer and a handful of other firms have taken control of the world’s food supply by restricting the options available to farmers. Vandana Shiva, philosopher and crop biotech critic, calls this “seed slavery”:

Seed slavery is ethically important to address because it transforms the Earth family into corporate property. It is ecologically important because with seeds in the hands of five corporations, biodiversity disappears, and is replaced by monocultures of GMOs. In our times some corporations think it is alright to own life on earth through patents and intellectual property rights (IPR). Patents are granted for inventions, and life is not an invention. These IPR monopolies on seeds are also creating a new bondage and dependency for farmers who are getting trapped in debt to pay royalties.

A recent series of mergers and acquisitions involving the world’s biggest biotechnology firms has only stoked fears of consolidation in seed production, a market once dominated by smaller, family-owned operations. In September 2017, former competitors Dow and DuPont Pioneer finalized their $130 billion merger into DowDuPont, now known as Corteva. A month later, Chinese firm ChemChina completed its purchase of Swiss chemical company Syngenta. In June 2018, German pharmaceutical giant Bayer acquired Monsanto for $63 billion

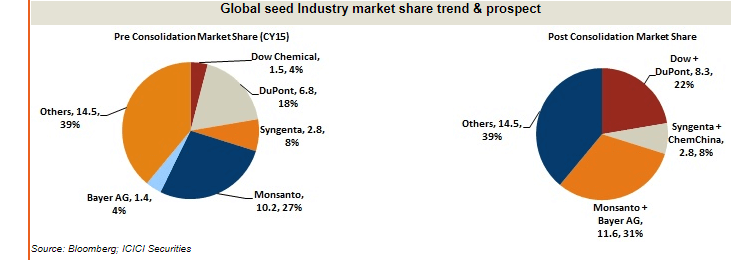

The US Justice Department only allowed Bayer to purchase Monsanto after the German firm sold its $9 billion crop sciences division to BASF, another competitor. These changes of ownership nonetheless represented a significant consolidation of the biotech seed market, with a 2017 estimate from Bloomberg and ICICI Securities suggesting that these three companies now represent more than 60 percent of the global seed market.

This consolidation, which began in the early 1990s with Monsanto’s acquisition of three smaller seed companies, was designed, in part, to supply the companies with the germplasm needed for the research that fuels seed development. According to the USDA, “proponents of the mergers argued that firms needed greater scale to invest in and support research, and that the mergers by creating more balanced portfolios of seed and chemical businesses would spur greater combined seed/chemical innovations.”

Opponents of the mergers argued that reduced competition would incentivize the remaining seed companies to raise their prices and cut research and development investment. That has not proven accurate. Since 2012, the profits farmers earn from selling their crops have declined. These slumping commodity prices have prevented seed companies from charging more for their products, because farmers simply can’t afford to pay more.

Overall, consolidation in the global seed market has not stifled innovation or spiked the prices farmers have to pay for seeds, according to a December 2018 study conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The study data came from surveys of farmers and seed distributors and expert estimates of market concentration. Instead of relying on global aggregates, which provide little information about conditions in individual seed markets, the authors had access to statistics for maize, soybeans, wheat and barley, rapeseed, sunflower, potato, sugar beet, and cotton in specific countries. Commenting on the study in February 2019, OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate Koen Deconinck explained

[T]he analysis did not find evidence of higher seed prices in markets with higher levels of market concentration …. [T]he study did not find any evidence that higher levels of market concentration reduce innovation ….

In a May 2019 Global Food Security Article, Deconinck added:

These data allow a more informed debate on the extent, causes, and potential effects of market concentration. The data indicate important differences across crops and countries in the level of concentration, but show no systemic evidence for harmful effects on prices or innovation.

Industry consolidation has also been criticized by some researchers who say it hinders the development of sustainable agriculture. Among critics is Phillip Howard, from Michigan State University’s Department of Community, Agriculture, Recreation and Resource Studies:

This consolidation is associated with a number of impacts that constrain the opportunities for renewable agriculture. Some of these include declining rates of saving and replanting seeds, as firms successfully convince a growing percentage of farmers to purchase their products year after year; a shift in both public and private research toward the most profitable proprietary crops and varieties, but away from the improvement of varieties that farmers can easily replant; and a reduction in seed diversity, as remaining firms eliminate less profitable lines from newly acquired subsidiaries.

Howard does not provide evidence to back up these claims and it is difficult to verify them because of numerous unknown factors, including proprietary information from these companies, accurate sales data from much smaller competitors and data on the amount of non-commercial seeds used in farming. In 2013, Monsanto, then the world’s largest seed company and now owned by Bayer, pegged its own share of the worldwide seed market at 5 percent, noting that there are many crop areas in which the company has little or no participation. When asked by the Genes and Science in June 2016 for further clarification, the company replied:

Aggregate commercial sales by all seed companies only account for about forty percent of the total volume of seeds used globally. Of those commercial seed sales, two-thirds of the seed volume comes from private breeding programs and one-third comes from national or public institutions. The remaining non-commercial seed volume is seed saved and replanted by farmers. As for commercial seed, the competition is quite robust as more than 1,000 separate seed companies supply the many types of commercial seed that are sold globally. Monsanto participates in only a few crops, with the two largest being corn and soybeans. While Monsanto is one of the largest commercial seed companies, even in those crops the company probably accounts for less than one-third of global commercial volume.

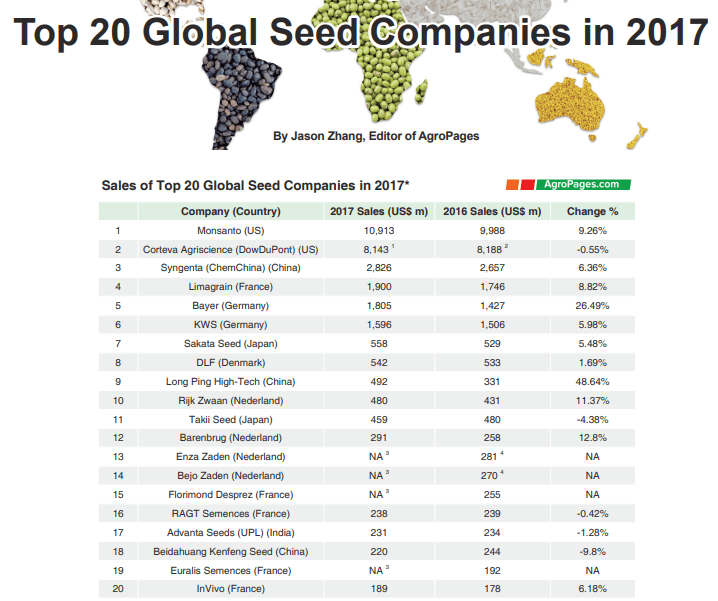

Global data makes it clear that Monsanto controls the largest share of the global seed market at about 34 percent, or more than one-third of the top 20 companies based in 2017 sales, far less than what many critics claim. DuPont was next at approximately 25 percent; Syngenta controlled less than 9 percent; Bayer slightly more than 5 percent.

The situation in the United States, where the footprint of the biotech corporations is much larger, particularly in row staple crops, is different. Roughly 95 percent of all corn and soybeans planted are genetically engineered. The top companies are responsible for most of those sales. In 2018, for example, Bayer and DowDuPont controlled 75-80 percent of the corn and soybean markets, according to analysts.

Critics complain that this dominance by a handful of major corporations which sell patented seeds gives the industry control of research and development, a charge that has been leveled at all agricultural firms, but most pointedly at Bayer, particularly after its purchase of Monsanto. This concern was even raised historically by one of Monsanto’s former competitors, Dupont Pioneer, now part of Corteva, in 2010 while the two firms were fighting over a licensing deal. Monsanto, an early innovator in the field, sells licenses to its competitors, allowing them to use traits developed by Monsanto. Through those agreements, Monsanto biotech traits can be found in most of the corn and soybeans planted in the US. In a report to the Department of Justice, Dupont wrote:

The ag biotech trait market is firmly in the grip of a single supplier, acting as a bottleneck to competition and choice… it also threatens the global goals for agriculture in the 21st Century doubling the world’s food supply by 2050.

At the heart of the concerns are the patents that protect the seeds and traits developed by the extensive research arms of the biotech companies. The patents and end-user agreements, regulating how seeds may be used, have become more common in recent decades, despite the fact that hybrid seeds have been sold since the 1930s. Farmers must purchase new seeds each year. (Many maintain that is what farmers would prefer to do anyway, as patented seeds generally produce better yields, making up for their higher cost.) And while these patent protections are heavily used by the large biotech firms who sell to the conventional and organic seed markets, they also are employed by some exclusively organic seed producers as well.

Some analysts, like futurist Ramez Namm, have challenged the argument that major chemical and agriculture companies have a lock on the future of the seed supply, for one very specific reason: patents end. The patent for Roundup, the trade name for the chemical glyphosate, which is paired with herbicide-resistant crops, expired years ago, and there are now many competing manufacturers. Patents for Monsanto’s first commercial genetically modified crop, Roundup Ready Soy I, expired at the end of the 2014 growing season.

The University of Arkansas has released free, replantable versions of Roundup Ready Soy. Any farmer can take this seed, plant it, save it, and replant seeds from the resulting crop for future years—the very seed saving scenario that critics say is at the heart of their concerns about corporate concentration. However, others have pointed out that this development will provide only limited additional options to most farmers, many of whom depend on international export markets. These specific unpatented GMO seeds may not be accepted for export by China or other foreign markets, meaning the global regulatory structure might unwittingly keep in place monopoly practices. Researchers are also developing generic insect-resistant corn, a previously patent-protected trait, that could cut seed prices for farmers while preserving crop yields. The new variety is expected to hit the market by 2021, pending EPA approval.

Over the years, there has been considerable complaining among critics, and some in the scientific research community, over access restrictions that have resulted from the patents and licensing agreements. Among other things, the agreements stipulated that seeds cannot be used for research without the approval of the company. The industry defended the practice as part of its efforts to protect intellectual property from competitors and piracy. This regulatory reality limits the promise of so-called open source GMOs.

This prompted a mini uprising in 2009, when a group of corn scientists accused biotech companies of standing in the way of research. In a statement to the Environmental Protection Agency, they said that because of those policies: “No truly independent research can be legally conducted on many critical questions.” The effort prompted an editorial in Scientific American urging the companies to end the restrictions on academic research:

It would be chilling enough if any other type of company were able to prevent independent researchers from testing its wares and reporting what they find imagine car companies trying to quash head-to-head model comparisons done by Consumer Reports, for example. But when scientists are prevented from examining the raw ingredients in our nation’s food supply or from testing the plant material that covers a large portion of the country’s agricultural land, the restrictions on free inquiry become dangerous.

That article is still cited frequently by GMO critics, although the access situation has improved significantly since 2009. The scientific community does not have unfettered access to seeds, but many of the companies have reached agreements with universities, loosening restrictions. Monsanto, for example, offers licenses, a policy it said was in place even before the 2009 dust-up, granting access to its commercial products for researchers at 100 US universities:

The blanket agreement allows university scientists to work with Monsanto’s commercial seed products without contacting the company or signing a separate contract for each study. This blanket agreement the Academic Research License (ARL) enables academic researchers to do research with commercialized products with as few constraints as possible. ARLs are in place with all major agriculturally-focused US universities about 100 in total.

In 2013, one of the original complaining scientists, Elson Shields of Cornell University, was asked if things have improved. He told Nathanael Johnson of Grist:

If you are at a major agricultural school that’s negotiated an agreement with the companies, it’s working fine. Each company has to decide how many universities to make those agreements with. What justification they have and why they pick one over the other, that’s above my pay grade. It may be that they know there’s a scientist whose work they don’t like, so they don’t choose that university.

The development of gene-edited crops, made possible by CRISPR-Cas9 and other new breeding techniques (NBTs), will likely spur additional competition in the oligopolistic biotech seed industry in the coming years. It has been estimated that it takes 8-13 years and $135 million to bring a transgenically developed crop to market. But this breeding dynamic stands to change, now that many national regulators are taking a hands-off approach to crops developed through NBTs.

Gene-edited crops, which typically don’t contain DNA from other species, are lightly regulated compared to their GMO predecessors in 13 countries, including the US, Canada, Brazil and Australia. This approach has enabled public universities and smaller private companies to begin developing new seeds for farmers to choose from. Since 2016, the USDA has approved dozens of gene-edited crop varieties, including corn, soybeans, tomatoes, pennycress and camelina. The first gene-edited soybean, developed by Minnesota-based biotech startup Calyxt, entered the US food supply in March 2019.

Significantly, the same activists, Vandana Shiva for instance, who oppose corporate domination of the food supply also staunchly reject crops developed from New Breeding Techniques that smaller firms are using to gain a foothold in the seed market. In Europe, environmental critics of biotechnology convinced politicians to regulate gene-edited crops just like GMOs, based on legislation from 2001. Biotech experts argue that these kinds of restrictions on CRISPR and other NBTs will prevent public universities from researching and developing new crop varieties, including plants that can better handle the vagaries of climate change, reduce chemical usage, or even prevent diseases—such as CRISPR wheat that could be safe for celiac patients to consume.